By the last

quarter of the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution, famine and

starvation had drawn many families away from the country toward industrialized

cities such as Liverpool, Birmingham, Glasgow and London and as a result all

were overrun with crime. The application of photography to bureaucratic and

surveillance technology within an increasingly centralized government body

unsure of how to maintain social order within its own expanding industrialized

cities was, by the 1870s an issue of utmost importance. Increasingly, before

the creation of a centralized police force many localized forces had made

attempts of decreasing the chances of recidivism in the criminal population

through the means of a photographic identification system. However without a

centralized police force nor a combination of bureaucracy and photography these

rarely worked.

The ways

and means in which the state identified and surveyed the criminal body in the

19th century was employed using older ideas of physiognomy and

phrenology and applying it to photography. These images were dissected, cut up

and codified into an order, which could be filed away and brought out for later

scrutiny and identification by a series of trained professionals. In other words,

the body of the criminal was made an archive.

Eliza

Farnham became one of the first to apply photography to the surveillance of

others. In 1846, in the United States, her publication, Rationale of Crime, used engravings made from Dageurreotypes

made by Mathew Brady. Her theories

incorporated ideas of physiognomy and phrenology, made fashionable by

Franz Josef Gall in the early 19th century, which had already set

unsurpassable distinctions between lower and upper classes through “zones of

deviance and respectability” in interpretations of the shape of the skull.

Farnham believed that her studies could have a reformative effect on her

subjects, but by dividing them according to race, ethnicity, gender, class and

age, and by providing commentary upon their skull shapes, she automatically

separates them into the ‘type’ of the surveyed.

In England,

during the 1850’s, Dr. Hugh Welch Diamond became one of the first people to

apply photography to the surveillance of others, albeit with humanistic intentions.

Diamond was the residential superintendent of the Surrey County Lunatic Asylum

from 1848 to 1858 and it was there that his experiments with photography and

mental illness began. Photography was generally believed to be the answer for

the need to legitimize the burgeoning pseudo-science of physiognomy championed

by Johan Casper Lavater in the eighteenth century.

Utilising

Frederick Scott Archer’s wet-colodion process, Diamond set about capturing the

female inmates of the Surry County Lunatic Asylum. Diamond was an advocate of

visual imagery as therapy for his patients and was generous in his use of

photography, allowing for the self-reflection required in order for the patient

to view and comment upon their own rehabilitation.

His paper

to the Royal Society in 1856, listed three possible applications of his

photography to the “mental phenomena of insanity”; A.) as a method of treating

the physiognomies of the mentally

ill for study, B.) of treating the mentally ill through the presentation of an

accurate self image, and, most importantly here C.) for documenting the

faces of patients to facilitate identification for later readmission and

treatment.

Adolphe

Quetelet believed that statistical data could identify a composite or average

man through large aggregates of statistical data. In his 1835 treatise ‘Sur

l’homme’, Quetelet relied

upon the central conceptual strategy of social statistics in order to seek

statistical regularities in birth, death and crime. From Quetelet on, social

statisticians become obsessed with anthropometrical researches, focusing both

on the skeletal proportions of the body and the volume and configuration of the

head.

Francis

Galton believed in statistical analysis also but his research was based upon an

unwavering belief in the moral degeneracy of the lower classes. Between 1877

and 1896 Galton produced a series of images that would influence eugenics into

the 20th century. Galton superimposed photographs of varying ethnic

and racial ‘types’ such as Jewish, Irish and African men, women and children on

top of each other, creating a composite image. This resultant, blurry image was

identified by Galton as the definitive description of each ethnicity and would

be used as a basis and an argument for the social betterment through breeding.

Here the body was codified and given order according to a predetermined and

biased set of instructions. Like the archive, photography is only given a

voice by those that wield the power. Sometimes the archive is silent and

sometimes it is loud.

Alphonse

Bertillon was a file clerk in a Paris prefecture in 1893 when he began to

establish what would become known variously as the Bertillon system,

Bertillonage and the Signaletic notice. Up to this point no perfect system had

yet been developed to decrease recidivism in criminals, partly due to no

systematized filing system being agreed apon by differing bureau’s and partly

due to the criminals ability to change thir appearance. Desperate to make a

name for himself in the burgeoning world of criminal identification and to

impress his Anthropometrist father, Bertillon devised a system which combined

both anthropometric data and photography into one taxonomic system.

Upon

entering the prefecture, the suspect would firstly be measured according to set

requirements that Bertillon regarded to be constant in an adult body, then

combined with a shorthand verbal description of distinguishing marks.

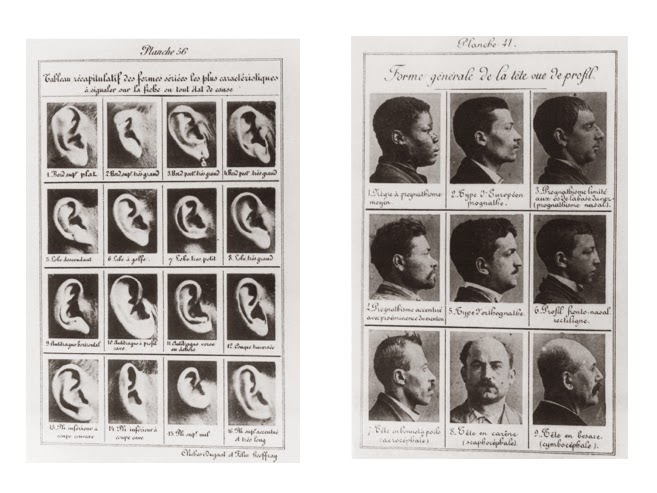

For

photography, Bertillon insisted on the maintenance of a standard focal length,

even and consistent lighting and a fixed distance between sitter and camera. He

had the sitter photographed in both profile and frontal views for ease of

identification by other sitters. He organized grids of the male head using

sectional photographs, as the brow largely remains the same throughout life. He

did the same with the ear, which like the fingerprint, rarely changes and is

unique.

Bertllon

sought to reinvent the practice of physiognomy using the cold, hard science of

statistical data. The camera is integrated into a larger ensemble which could

be described as a sophisticated form of the archive in which the central

artifact wielding the most power becomes the filing cabinet itself. Bertillon

devised a classification schema for human beings, which, much like the archive

itself, ordered, separated and taxonomised individual cases into an aggregated

system of identification. Unlike Francis Galton or Eliza Farnham, Bertillon was

not influenced by a biased ethnographic interpretation of racial or ethnic

types. His form of statistical analysis paved the way for the cold, hard

objectivity of 20th century police-work unadorned by class or racial

interpretations.

“What we

have in this standardized image is more than a picture of a supposed criminal.

It is a portrait of the product of the disciplinary method: the body

made object; divided and

studied;

enclosed in a cellular structure of space whose architecture is the file-index;

made

docile and forced to yield up its truth; separated and individuated; subjected

and made subject. When accumulated, such images amount to a new representation

of society.”

- John Tagg, The Burden of Representation.

Bibliography

Dalston, Lorraine and Gallison, Peter, ‘The Image of Objectivity’, Representations 40 (Fall, 1992), pp.

81-128

Popple, Simon ‘Photography, Crime and Social Control’, Early popular Visual Culture, 3:1 (2005),

95-106.

Pearl, Sharrona ‘Through a Mediated Mirror: The Photographic

Physiognomy of Dr Hugh Welch Diamond’, History of Photography, 33:3 (2009), 289-305.

Sekula, Allan, “The Body and the Archive”, October, 39 (Winter, 986),

pp.3-64

Tagg, John, The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies

and Histories,

Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1988